A study by the Institute for Integrative Systems Biology (I2SysBio), a research centre at the UV Science Park, reveals that the worm Caenorhabditis elegans develops an acquired immunity against latent viruses. This new mechanism opens the door to the development of new therapies against viral infections and control systems against future epidemics

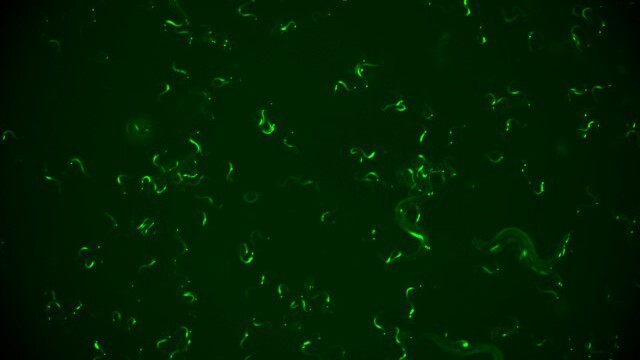

A study by the Institute of Integrative Systems Biology (I2SysBio), located in the scientific-academic area of the University of Valencia Science Park and joint centre of the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) and the University of Valencia (UV), shows that the Orsay virus, that naturally infects the nematode (roundworm) Caenorhabditis elegans, establishes latent infections that remain dormant and are reactivated at different stages of the animal’s life. The results, published in the journal Nature Communications, show how these initial infections produce an immune memory that allows the body to protect itself against reinfections, even when they come from different strains of the virus.

Orsay is an RNA virus that, despite its similarities with other pathogens such as those causing avian influenza or COVID-19, does not affect humans but its only known host is the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. It is a worm widely used as an experimental model in research because of its genetic similarity to humans, with whom it shares more than 80% of its proteins. With these initial elements, the research team conducted a study to understand the mechanisms of viral persistence, reactivation and immune response of C. elegans against its natural parasite.

"Discovering an evolutionarily conserved mechanism to understand why the interaction between a host and its viruses results in latent infection or acute infection is relevant for the design of new therapies and the control of epidemics.", Santiago F. Elena, I2SysBio researcher

The work led by I2SysBio researcher Santiago F. Elena shows that the immune response of the animal against the virus depends on a mechanism called RNA interference. This system, key to the antiviral defense of this type of nematode, consists in the degradation of messenger RNA (mRNA), the molecule that carries genetic information for the synthesis of new proteins. This degradation process allows genes to be specifically turned off, thus preventing the message of a gene from being translated into a protein. Through the analysis of this mechanism, researchers were able to observe how previously infected animals were able to contain viral replication after a second exposure, suggesting an induced immune response.

In addition, the study points out that this immune response is regulated in two ways. On the one hand, by a generalized reprogramming of the transcriptome, the set of all mRNA molecules in each cell. This process involves an alteration in the quantities of mRNA, thus altering the structure, metabolism and function of cells. On the other hand, it is mediated by alterations in the landscape of small RNAs, not messengers but with a regulatory function in stressful situations, such as viral infections. "When we talk about these alterations, we are referring to any change in small non-coding RNAs, that is, in short molecules which do not translate into proteins but play a key role in the regulation of gene expression," explains Santiago F. Elena.

The immune response decreases with age

In 2024, I2SysBio already succeeded in describing the response of the nematode C. elegans to a chronic infection of the Orsay virus from birth until it reaches sexual maturity, with the highest resolution to date. Now, the new study not only shows how the animal remembers the immune response to the virus to cope with new infections, including different strains of the virus, but also finds that the intensity of this acquired response decreases with age.

This cross-protection phenomenon is explained by the action of the RNA interference mechanism. This mechanism is based on generating small interfering RNAs (RNAi) from the genome of the first virus it infects, which a complex cellular machinery then amplifies and uses as a guide to block the gene expression of a virus, genetically related to the first, that it would infect later. This type of immunity, ancestral in evolutionary terms, is found in both plants and animals.

"Immunity changes with age in all living beings, the elderly being generally resistant to past infections, but with worse responses to new ones." Santiago F. Elena, I2SysBio researcher

"Immunity changes with age in all living beings, and elderly individuals are generally resistant to past infections but have worse responses to new ones," explains the I2SysBio researcher.

The study also suggests that the struggle for resources and cellular machinery between the RNA molecules produced by the body itself (endogenous) and the RNAs introduced by the virus during an infection could modulate the effectiveness of the RNA interference mechanism (RNAi), on which the immune response of C. elegans depends. This finding opens new avenues for investigating how viruses interfere with host defense mechanisms.

"Discovering an evolutionarily preserved mechanism that allows us to understand why the interaction between a host and its viruses results in a latent infection or an acute infection is relevant for the design of new therapies and the control of epidemics," concludes Santiago F. Elena.

Source: Delegation CSIC Comunitat Valenciana

Castiglioni, V.G., Villena-Giménez, A., Herek, D., González-Sánchez, A., Toft, C., Gómez, G.G., Elena, S.F., Latent infection of Caenorhabditis elegans by Orsay virus induces age-dependent immunity and cross-protection. Nature Communications. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62522-2

--

Recent Posts